by Aaron Crider, with a response by Steve Sanford

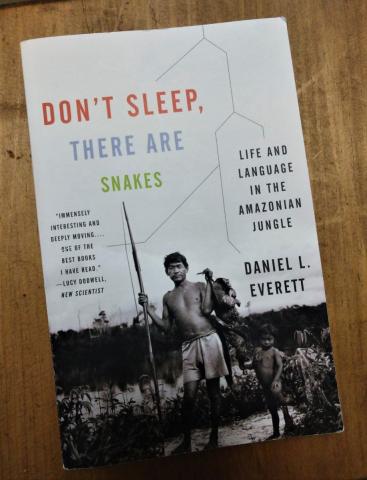

This writing was provoked by the book Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes, where former Bible translator Daniel Everett tells about his life and language work among the Pirahá people in the Amazonian jungle.

A few observations about the Pirahá culture and language will lead to what I really want to explore with you: why Mr. Everett, the missionary Bible translator, lost his faith in God.

Life and Language

“Don’t sleep, there are snakes!” The title of the book comes from an admonition heard every day in Pirahá , since it’s what they tell each other when dispersing for the night. Encouraging farewell, isn’t it?

Tonal language. In Pirahá, every syllable has a relative pitch to the other syllables in the same word. Because of this, hunters in the woods can communicate with each other by simply whistling the words, which doesn’t scare off the animals like their voices would. A mother can hum a story to her baby.

No need for polite verbiage. Pirahá includes no socially polite words that function like our hello, goodbye, how are you?, I’m sorry, you’re welcome, and thank you. Their culture simply has no concept of such functions.

Happy as they are? Everett was deeply impressed with the happy, care-free, self-confident existence of the Pirahá.. An example of this is how they never showed anger. Even when a spouse ran off with someone else, the other spouse appeared to simply accept it, and went on with life. [1]

The here and now. The most pervasive cultural phenomenon Everett uncovered took a long time to figure out to his satisfaction. The concept was connected to a word the Pirahá used at the moment when someone or something appeared or disappeared. When the plane appeared in the sky, or the canoe disappeared around the bend: “xibipíío!”

Everett says, “Eventually, I realized that this term referred to what I call experiential liminality, the act of just entering or leaving perception, that is, a being on the boundaries of experience.”

The term is connected, Everett realized, with a cultural reality: The Pirahá almost never talk about anything they didn’t either see for themselves or hear from an eyewitness. “They seem to focus on the now, on their immediate experience.” The person in the canoe, once around the bend and out of view, is out of their immediate realm of experience.

Everett believes that this “immediacy of experience” principle accounts for many aspects of Pirahá culture, including the absence of history and folklore (which would involve a discussion of things outside of their immediate experience.)

Trying to understand this cultural feature became significant in Everett’s spiritual journey.

The Missionary’s Conversion

In the final chapter, Everett comes out with what he’s hinted at throughout the book: He is no longer a Bible translator, no longer a missionary, no longer a Christian.

We don’t want Jesus

“Hey Dan, I want to talk to you. The Pirahás know that you left your family and your own land to come here and live with us. We know that you do this to tell us about Jesus. But… we like to drink. We like more than one woman. We don’t want Jesus.” Then, referring to the previous American missionaries among them, this man added, “The others told us about Jesus. But we don’t want Jesus.”

Concerned that they just didn’t understand the Gospel, Everett hurried the translation of Mark’s gospel and recorded a native speaker narrating it. But the Pirahá, recognizing the voice on the recording, said, “We know that man has never seen Jesus.” With that, any interest in the recordings died.

Losing faith

When all other attempts to communicate the story of Jesus failed as well, Everett began to despair of ever communicating the Gospel to them.

Meanwhile, observing their preoccupation with the here and now, Everett was formulating his “immediacy of experience” theory. He became convinced that Pirahá culture and language are inherently unable to engage with anything outside their experience.

This led Everett to conclude that the historic Gospel narrative cannot be communicated to the Pirahá , and therefore the Gospel itself cannot be for them.

As you can imagine, from acknowledging a limited Gospel, it was a small step for Everett to lose his own faith. If the Gospel of Jesus is not for everyone, how could its claims be true at all? Today he no longer counts himself a Christian.

Perspective matters!

Everett’s encounter with the Pirahá illustrates an observation from Greg Pruett of Pioneer Bible Translators. “Each culture develops a world view only complicated enough to explain all of the experiences and information they will encounter in their setting. Missionaries and especially Bible translators encounter the broadest possible range of different contexts in the world.”

How can those sent to work in new and strange cultures be assured that the Gospel of Jesus Christ IS for those people who seem impossible to reach?

We asked Steve Sanford, a consultant for All-Nations who serves in Ethnos360 and helped evangelize the Joti, another remote Amazonian tribe. He shared the Joti story at our EXPLORE 2019.

Mr. Sanford’s response underscores a foundational principle: The perspective and understanding we bring to the work God entrusts to us can drastically affect the outcome.

Steve Sanford Responds

I noted several similarities between the Joti and Pirahá languages. Joti do not have words like hello, goodbye, I’m sorry, you’re welcome, or thank you. This is common in languages we have encountered. The Joti did not say “‘I am sorry” or “thank you” until after the Bible got there and they were believers. I have always believed that this is due to their lack of a knowledge of God. Paul describes the Gentiles who turned from God by saying “neither were they thankful.” Unthankful people do not have a word for thank you. If the Joti language ever did, it was lost.

I don’t have a hard time believing that their culture is totally wrapped up in the here and now, and that they have little interest in talking about anything that is not in the immediate. The Joti were not that way to the extreme that he describes the Pirahá, but they were similar. I attributed that to the fact that they simply did not have the luxury of being concerned with much beyond the here and now. They had to sustain themselves, and their families, for today and perhaps tomorrow. That is what every day was built around. So their conversation was heavily focused on these realities. Could the Pirahá language, over time, change to reflect an “immediacy of life” focus in their culture? I can believe that.

Further, I see a phenomenon like this as perhaps an intentional and effective tool of the enemy. If the Pirahá develop a cultural aversion to talking about anything that does not affect them in the here and now, that would be an effective way to keep them in darkness. What Everett was seeing could be part of a long term effort of God’s enemy to build barriers to Gospel understanding.

It’s of interest to me what they said to Everett about Jesus. They rejected a person named Jesus who would prevent them from having multiple women and drinking alcohol. What did they actually understand about him? What did they understand about God The Father, about themselves, about sin, etc.? Sounds like previous missionaries had told them something. Later they had a gospel with apparently no historic background information and no systematic teaching to help them understand the account. With that, they apparently understood enough to know Jesus will take away our drink and our extramarital affairs. Interesting that people who can only think and communicate about the here and now understood the future ramifications of what they were hearing about Jesus.

What he experienced with the Pirahá is no different than what we in Ethnos360/NTM experienced in many tribal groups. A rejection at worst, or a synchronization at best, of a message people had no foundation upon which to understand correctly.

It may take some creative linguistic efforts to overcome generations of language adaptations the enemy designed to avoid conversation about abstract concepts. And it may take some creative ways to generate interest. But when the message is communicated in an understandable way, with foundation and contrastive explanation, I believe the Spirit of God could make his message clear to the Pirahá.

It seems to me that Daniel Everett reached a very sad and incorrect conclusion. He observed a culture that had developed in darkness over thousands of years, a culture that was heavily influenced by God’s enemy to avoid any thought of anything beyond the immediate, a language that had adapted to that perspective, and as a result concluded that God must not exist.

My conclusion would have been the opposite. Everett was witnessing clear evidence that God’s enemy is at work to do exactly what God’s Word said the enemy would be at work doing, “blinding the minds of unbelievers.” Evidence of God’s enemy at work is evidence of God’s Word being true. Every missionary should expect to see this in some form.

Conclusion

At All-Nations, we believe the perspective and understanding we bring to the work can drastically affect the outcome. Our goal is to facilitate training that prepares church-planting teams to see beyond the apparent impossibilities of their task to the unlimited redemptive power of God.

I am saddened for Mr. Everett and his failed mission. God’s heart bleeds for the Pirahá and many other peoples the enemy has kept in darkness.

The challenge is now ours. Will you pray for us?

And perhaps also for the Pirahá ?

[1] Interestingly, Steve Sanford shares a contrasting perspective of the same phenomenon in this talk about reaching another jungle tribe. What underlying issues did Everett fail to uncover regarding this and other aspects of their seemingly happy existence? ↩

Click here for a downloadable PDF of this article.